The grounds of the Deserted Village are open every day, dawn to dusk.

The Church/Store and Masker’s Barn are wheelchair-accessible, including restrooms.

About 1736, Peter Willcocks built a sawmill along the Blue Brook to produce lumber, which would be needed by farmers as they settled this frontier area. The sawmill operation cleared hundreds of acres of forest.

In 1845, David Felt bought 760 acres of land and built a printing factory along the brook. He built an entire village on the bluff above the brook to support the mill operation, and by 1850, 175 people were living in Feltville. After Felt retired in 1860, other business ventures were tried here but failed, and the village became deserted for a short time.

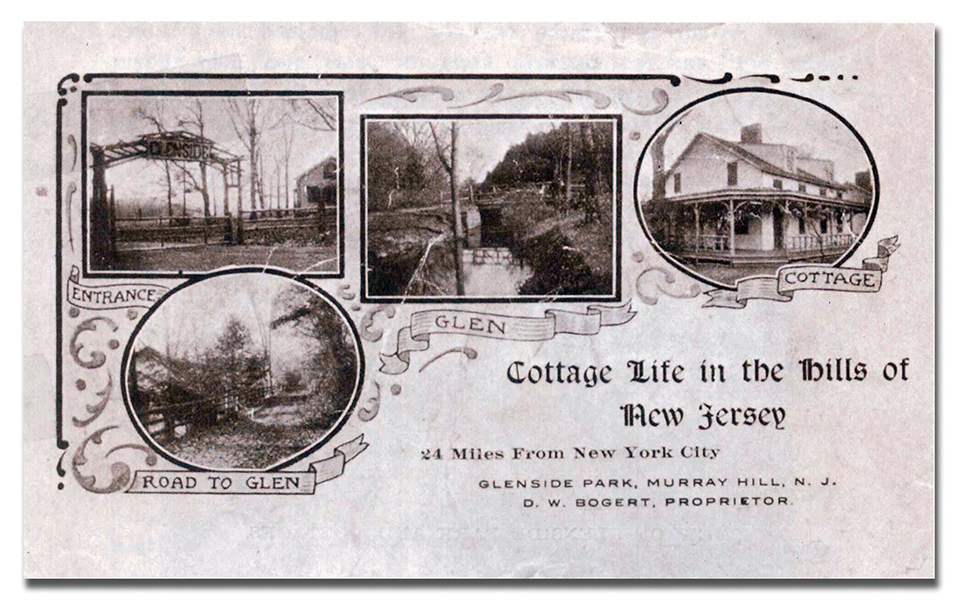

In 1882, Warren Ackerman bought the property and converted the former mill town into a summer resort, named Glenside Park. The popularity of mountain resorts waned as the Jersey shore gained popularity, and Glenside Park closed in 1916.

Soon after the Union County Park System was formed in 1921, this area was incorporated into the Watchung Reservation — one of America’s first county parks. This unique historic resource is listed on both the State and National Registers of Historic Places.

Preservation & Restoration

While there is still much work to be done, the preservation of this village could not have been accomplished without support and funding from the Union County Open Space, Recreation & Historic Preservation Trust Fund; the New Jersey Historic Trust; and other contributors.

More than $6.5 million has gone towards building infrastructure, and stabilizing and renovating the historic buildings. Masker’s Barn and the Church/Store are the cornerstones of the Deserted Village restoration project. Gas, water, sewer and electrical lines are in place, enabling preservation of additional buildings and use of them by the general public. House #7 has been stabilized and ongoing work is in progress on House #4.

For the safety of pets and enjoyment of this area, visitors are asked to adhere to the County ordinance that dogs be restrained by a leash.

Please do not walk onto the porch of any house in the village, except the restored Church/Store building, pictured above. Some of the houses here are inhabited; others have structurally weak porches.

- The grounds of the Deserted Village are open every day, dawn to dusk.

- The Church/Store and Masker’s Barn are wheelchair-accessible, including restrooms.

Interpretive panels are located throughout the Deserted Village. Union County received an Achievement Award from the National Association of Counties (NACo) for the panels, recognizing the contribution to the Arts, Culture and Historic Preservation of the county.

A Self-Guided Walking Tour of the Deserted Village

Over the course of three centuries, this area has been a farming community, a quasi-utopian mill town, a deserted village and a summer resort. This walking tour will help you understand the history of the village, its buildings, archaeological remains and more.

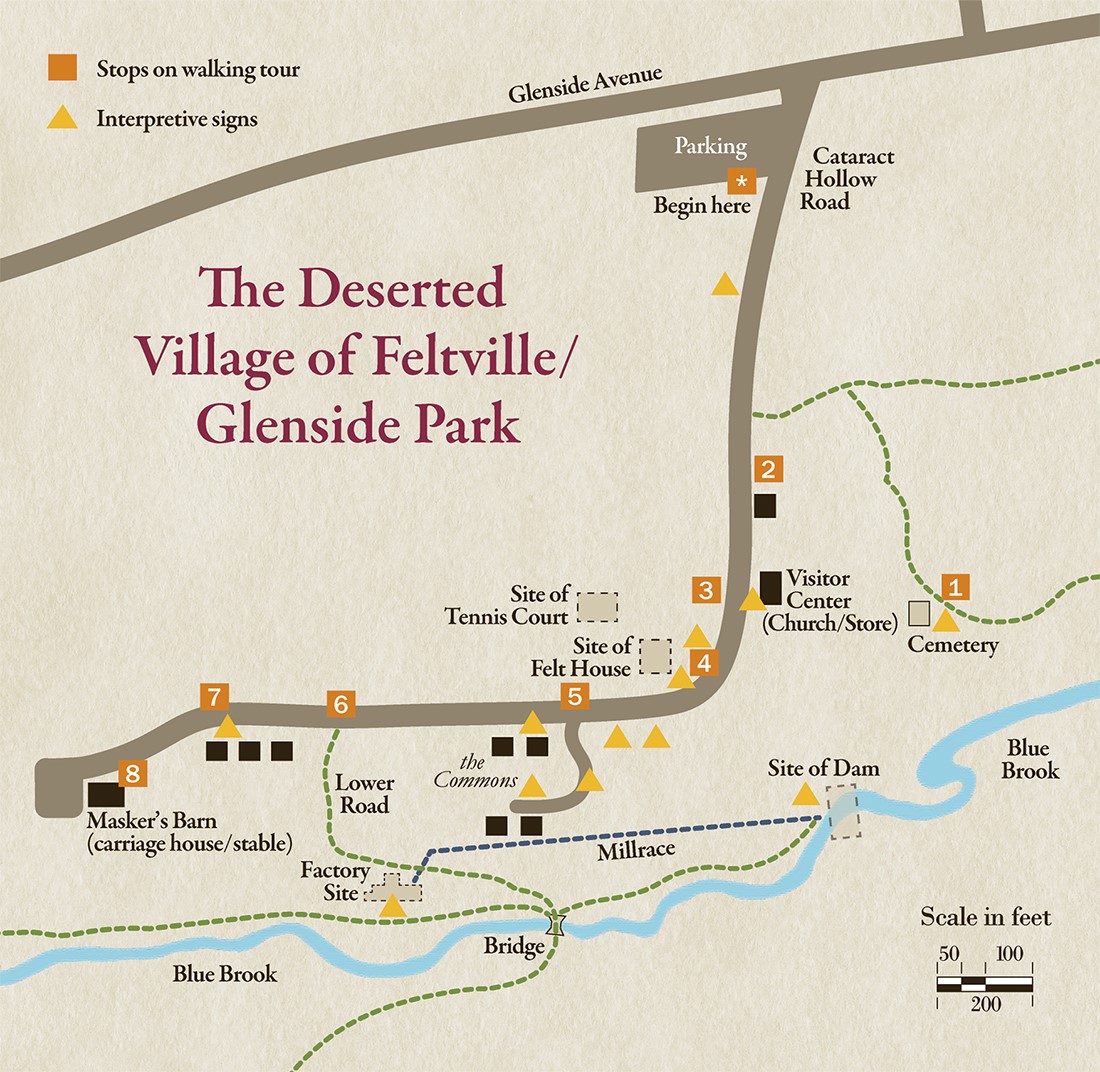

Approximately a mile long, the tour starts and ends in the parking lot just off Glenside Avenue. See the map for orientation and tour stops.

A brochure providing this walking tour is usually available at the brown kiosks (one in the parking lot just off Glenside Avenue, the other just past the Church/Store). The Walking Tour also appears below. The Walking Tour brochure can also be downloaded here.

Walk down Cataract Hollow Road to the first bridle trail crossing, and turn left onto that trail. Then turn right onto the first hiking trail and follow it to the village cemetery.

The first known colonial settler of this area was Peter Willcocks, an Englishman who moved to this area around 1720 from Long Island. Peter built a dam across the Blue Brook to harness the brook’s water to power a saw mill which he constructed. Clearing trees from the surrounding forest, Willcocks produced lumber that was sold to settlers developing farms in the surrounding frontier countryside. In the fields created by the removal of trees, the Willcocks family farmed the land for the next century, attracting other settlers, such as the Badgley and Raddin families.

Of the five headstones seen in this cemetery today, only one is original. The others were placed here in the 1960s to replace missing stones. None of the headstones stand over the actual grave of the person named. Two of the headstones are for the same person, John Willcocks. It is believed that about two dozen people were buried here in the Willcocks family plot.

At the far left, a headstone commemorates Phebe Badgley Willcocks, who met and married Peter Willcocks while both were living on Long Island. When she and Peter moved here to the second Watchung Mountain, her brothers and sisters came with them and settled in an area on the First Watchung Mountain, which today is the Scout Camping area near Trailside Nature & Science Center, on the other side of Watchung Reservation.

The original stone near the right, and the newer stone to the right of it, commemorate John Willcocks, one of five children of Phebe and Peter. The old stone bears a fairly typical Puritan-influenced design called the “death’s head” by archaeologists. This style originated in New England and is typical of 17th- and 18th-century tombstones throughout the Northeast.

Although the dates on the stones seem to indicate that Phebe and her son died on the same day, it is currently believed that Phebe died in June of 1776, but her death was not recorded until after her son John’s death. He served in the New Jersey militia and is thought to have been mortally wounded during the retreat of General George Washington’s army from Fort Lee.

Return along the same path, back to Cataract Hollow Road. Turn left and walk down the road to the first house (House #1).

David Felt owned a stationery business in New York City, with a store in Manhattan and a factory in Brooklyn. In 1844, he began buying up property here from Peter Willcocks’s descendants in order to establish another factory. Within two years, from 1845 to 1847, Felt built a mill down along the Blue Brook, two dams to supply water power for his mill, and an entire town here on the bluff to house all of the people who would work in that mill. That town became known as Feltville.

Like many of his contemporaries in the Unitarian church, David Felt approached life with a desire to better the lot of his employees and peers, regardless of their station in life. In a time of exploitative labor practices, Feltville provided pleasant surroundings, in contrast with urban industrial cities like Paterson, NJ and Lowell, Massachusetts. Felt’s workers here had relatively spacious accommodations, yards for growing produce, a post office, and a school for their children. Some of these structures are now only visible as archaeological remains. The building in front of you was built to serve as the office for Felt’s business. As originally constructed, this building was only two-thirds its current size. It was expanded late in the 1800s, after its use changed from commercial to residential. As with all of the buildings here in Feltville, using one’s imagination is needed to visualize the buildings as they were first built in 1845, without the large porches and roof dormers added later

Continue walking down Cataract Hollow Road to the next building —the Church/Store (Visitor Center).

This building was built by David Felt to serve as the general store for his mill town. Six-hundred acres of fields around this site were being farmed. Harvested crops were sold to village residents at this store. The mill workers were presumably also able to buy meat from livestock that Felt raised, as well as the fruits of his apple and peach orchards. However, it is interesting to note that bone remains from the meals of some of Felt’s workers (recovered from a privy excavated in 1999) indicate that meat was more often obtained through local hunting and fishing; and contemporary descriptions of the village discuss gardens surrounding each of the workers’ houses. By 1851, a Post Office was established inside this building as well.

David Felt ran Feltville with a beneficent but stern hand, earning himself the paternalistic nickname “King David.” Village residents were required to attend religious services each week in a church on the second floor of this building, but were allowed to worship and practice religion in accordance with their own beliefs. Felt provided a minister of varying denominations each week to conduct the services, and eventually hired a non-denominational minister to remain in full-time residence.

Children were taught in a one-room schoolhouse which stood in the area that is now the parking lot at the top of Cataract Hollow Road. It is important to note that an average 12-year-old in a working-class family during Felt’s time was immediately recruited into domestic or factory labor. Felt’s free school and his provision of a liberal house of worship demonstrate that he was concerned to an unusual degree with the social welfare of his employees’ families.

Interestingly, the steeple (or belfry) seen here today did not yet exist during the period when this building was being used as a church. This building was the subject of the Village’s first full-scale restoration project, completed in 1998.

Continue your walk down Cataract Hollow Road. Stop at the split-rail fence, just as the road begins to curve to the right.

In 2004, archaeologists from Montclair State University’s Center for Archaeological Studies uncovered the foundation of David Felt’s residence. Formerly described as a ‘mansion,’ Felt’s humble abode was, in fact, no larger than any of the workers’ houses in the village.

Walk about 100 yards and stop at the next intersection.

The road to your left (south) is called the Lower Road, and the area including the four standing buildings is The Commons. This was the main block of housing for Felt’s managers, specialists and many of his mill workers. In a sense, it was the middle-class section of the village. In addition to the four houses you see now, there were four others here which have since been torn down or had burned. (In Felt’s time, there were three houses in the front row, and five along the back road.)

All of the cottages were connected by gravel-lined walkways running between the back and front porches. Archaeological work showed that artifacts recovered from these walkways were created and used in the late 19th century during the site’s later Glenside resort phase, while artifacts recovered below those date from Felt’s time. From the artifacts, archaeologists learned that people living in the eastern portion of Feltville were generally better able to afford fashionable housewares such as porcelain and whiteware than those living further west.

All of the houses in Feltville, regardless of size, were partitioned at their center, much as a duplex house is today. Each side had its own entrance and staircase. Fireplaces on the ground floor of all of the houses, and in the basements of the larger houses, were set back-to-back against a central chimney. With about 175 residents living in Feltville by 1850, and only 11 total buildings in which to house them, there were probably four families living in each of these larger houses, and two families in each of the three smaller houses that you will see further down the road.

Feltville thrived for 15 years under the paternalistic control of David Felt. In 1860, he was 67 years old. In August of that year, he sold Feltville to Amasa Foster and returned to New York City. Why Felt decided to sell his business and property in New Jersey at that time is not entirely clear. Some speculate that his decision was tied to the failing health of his brother, Willard, who had been managing the affairs in New York. In any case, as he left Feltville, David Felt is reported to have predicted, “Well, ‘King David’ is dead, and the Village will go to hell.” By 1872, Felt had sold most of his business and was filing for bankruptcy.

Over the next two decades, ownership of the property here changed hands six times. Several business ventures were initiated here at various times, including the manufacture of sarsaparilla, cigars, and silk. However, all were unsuccessful, and for a while the former mill town may have been abandoned. During this time it became known as the Deserted Village.

In 1882, Feltville was purchased at public auction by Warren Ackerman, a prominent landholder, for only $11,450, a fraction of its former worth. Ackerman converted Feltville into a summer resort and renamed it Glenside Park. All of the former workers’ dwellings were renovated. Dormers were added to the roofs of the larger houses to make the second-story spaces more livable. Wide porches with rustic, Adirondack-style cedar posts and railings were constructed, giving each building its own unique appearance for the first time.

Proceed further along Cataract Hollow Road to the dip in the road, where a bridle trail and stone wall turn off to the left. Stop here to read the next section, or go down the bridle trail to see the Blue Brook and the site of the former mill at the bottom of this hill – then return to this point.

At the base of this hill was the 3½-story mill that had been the center of life in Feltville. Water routed from a dam upstream flowed through a raceway and over a waterwheel on the side of the mill. The turning of the wheel generated twelve horsepower and was used to operate presses, polishers, and book-binding machines. Felt’s operation produced all types of business stationery, including blank journals and ledger books. Finished products were transported to Felt’s store in New York by Conestoga wagon.

During the Glenside resort period, Ackerman also was involved in raising fancy cattle. He used Felt’s vacant mill as a stable for his cattle, and built this road as a way to move his cattle up to the former farm fields for grazing. The abandoned mill was torn down in 1930, after it was deemed to have become a safety hazard.

Continue along Cataract Hollow Road, stopping in front of the third small cottage (House #12)

As with the other houses here, the interiors of these three small cottages were divided down the middle. The 1850 federal Census suggests that each of these cottages housed from six to twelve people, although their size is smaller than the other houses. House #12 gives us the best glimpse of a true mill worker’s house, with both of the original entry doors still intact. The back yards of these cottages have revealed many interesting archaeological features, including a two-seat privy, a thick spread of scattered artifacts, walkways corresponding with those of The Commons area, and a brick-lined well, located between the two westernmost cottages.

During the conversion from mill town to summer resort, the interior partitions were opened up to convert these buildings into single-family dwellings. A water supply and a steam laundry were constructed at a spring-fed pond further out along this road. Electric lights were installed along the resort streets. With indoor plumbing and electricity, residents of the village no longer needed oil lamps and chamber pots, so such items were taken into the back yards and dumped into the no-longer-used privy.

The privy, excavated by archaeologists in 1999, has a vault constructed of loosely laid basalt without mortar. It was very poorly maintained (one of its walls partly collapsed in the 19th century and was never repaired) and perhaps never cleaned, since the artifacts within it represented every time period of the village’s occupation.

Continue along Cataract Hollow Road a short distance to its end at Masker’s Barn.

Many of the summer resort visitors here were from New York, Orange and Newark. A barn was built here in 1882 to house horses and carriages which would be used to transport businessmen to the train station at Murray Hill, and thence by train to their jobs in Manhattan, while their families stayed behind to enjoy resort life.

While at Glenside Park, visitors could participate in many activities, including golf, tennis, croquet, baseball, fishing, and horseback riding. Glenside guests could dine at an inn established in one of the houses. Dances were held here in the barn.

Glenside Park flourished until 1916, when the hamlet began losing its appeal. The advent of the automobile permitted former patrons to travel further away from their homes, especially to the developing Jersey Shore area. For a while, the village became almost deserted again.

In the 1920s, the property was purchased by the newly-formed Union County Park Commission, and incorporated into the Watchung Reservation. The Park Commission began to rent out the houses, especially during the Great Depression, and had full occupancy until the 1960s. An Outdoor Education Center operated here and used several of the houses as classrooms until it closed in 1984.

This site was listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places in 1980. Stabilization work was performed on all of the buildings in 1992 using a New Jersey Historic Trust grant. Another Trust grant and funding from the Union County Open Space, Recreation and Historic Preservation Trust Fund enabled the restoration and rehabilitation of Masker’s Barn, completed in 2011, for use as a public assembly building, lecture hall and event-rental space.

To return to the parking lot, walk back uphill on Cataract Hollow Road.

The Deserted Village is one of more than 30 historic sites across Union County open to the public on the third weekend in October as part of the “Four Centuries in a Weekend” program. Visitors can take a guided tour, view exhibits in the Visitor Center (Church/Store), ride a hay wagon, and take part in other activities, free of charge.

“Haunted Hayrides” also take place at the Deserted Village in October, before Halloween, offering a fun mix of historical narrative, costumed characters and special effects. Tickets usually go on sale in mid-September.

Find information about all County programs on the Union County website: www.ucnj.org.

Masker’s Barn is available to be rented for events. Find photos, rates and reservation information here.